Final Portfolio (SOWK 304/305)

Module 1: Diversity and Anti-oppressive Practice

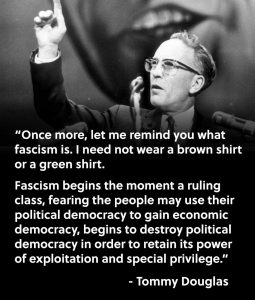

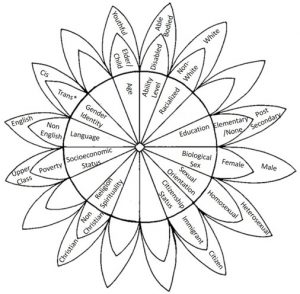

Critical and radical social work criticize traditional social work for maintaining and reinforcing oppression and inequality, as the social problems are understood as being a result of the individual’s coping, rather than why they need to cope in the first place (Mattsson, 2014). If government control erodes and democratic control of social policy fade, the benefactor becomes transnational corporations, international banks, and those with privilege (Bishop, 2015). A compromised civil society leaves open vulnerabilities within its social fabric in which intersectional attributes of an individual can (dis)privilege one person over another, increasing inequality. The lived experiences of individuals that have a diverse range of intersectional attributes provide insight into the varying degrees of oppression and social stratification that can exist in society (Mattsson, 2014). Uniting the various strata to end the existence of the strata is thus one of the goals of combating oppression. It also means reflecting on how we perpetuate and effectively challenge the systems that maintain oppression (Mattsson, 2014). To do so involves us challenging the schemas and discourses, that have been a part of our socialized experience, and examine how the thought systems are utilized to internalize compliance with power structures and make us complicit within our own social location, as well as apathetic to the social location of others (Cocker & Hafford-Letchfield, 2014; Mattsson, 2014).

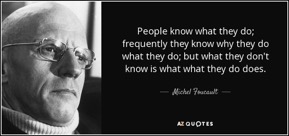

Foucault’s perspectives on dominant discourses as a means of social control thus become a critical component of how we as social workers make sense of where there is conflict, and how discourses are changed. It is also important to see who benefits from those changes (Cocker & Hafford-Letchfield, 2014). Similarly, the relationship between clients, professionals, and society, must be carried out with continual awareness of how our actions, and applications of learnings impact society. Do we reinforce stereotypes, give birth to new stereotypes, or create new forms of exclusion as phenomenon arise occur throughout our careers? Perhaps, from reflection on Bishop’s work (2014), analyzing the different discourses that keep oppression, or current structures, in place need continuous reflection to maintain an anti-oppressive approach. Strategies such as blaming the victim, stereotyping, or the myth of scarcity can be provided in a sociohistorical context (Bishop, 2015). I found it very interesting how Bishop unpacked the history of how violence took root in Europe, a continent that essentially colonized the world. This would fit in with Foucault’s concept of archeology (Foucault, 1995) and can provide a means to process structures within our work with individuals and examine how they maintain obedience to the status quo. Perhaps, we need to put greater weight on Bishop’s (2015) suggestion of the interconnections between various forms of oppression.

Module 2: Human Developments & Environments

I believe that scholars such as Annie Wegner-Nabigon (2010) do a very good job of walking between the line of cultural relevance and cultural meaning systems (Castillo, 1997) while bringing together indigenous and western schools of child development together. Seeking a third way to understand child development through the application of the indigenous medicine wheel with development theories was a very interesting way of looking at how to engage in a practice that blends the knowledge of two paradigms to create a more holistic vision. The same critical thinking can be said about examining culturally imperialist assumptions on attachment theory as outlined by Neckowaya, Brownleea, and Castellan (2007). In relation to becoming an ally, when we look at cultural genocide that took place in the conquest of Indigenous lands, we see a removal of indigenous cultural practices and replacement with colonial practices (Bishop, 2015). Reintegrating indigenous perspectives and knowledge systems into practice thus becomes the light for healing that will help re-establish ways in which we see human development from multiple paradigms grow. It may serve as one of the dimensions by which indigenous ways of knowing can continue to become increasingly accepted within the health and human service disciplines.

Related to the expansion of indigenous and alternative perspectives on child development are the concerns that arise from the commercialization of children. Critical thinking on the implications of environment for child development has not only on the wellbeing of the child & child-parent dyad in mind but also on society as a whole must be continually present in our interactions and interventions for social change. As noted by Bishop (2015), the consumerist wedge between child and parent may set up the child’s template for the use of power-over later in life. Being aware of that, we also need to be mindful that the use of power-over may come from a place of early childhood experiences, and not the intentional malice of the individual wielding the power. I feel that the reminder can serve to humanize individuals who may be misguided in the use of power. That provides an opportunity to lower our own defences and assumptions and explore the use of power with individuals. Not all individuals are necessarily ready to take the journey to explore that avenue, so we would need to work with the stages of change (Shebib, 2017). But, should we be working to help develop community members for social movements or social action, we have something we can investigate together early on with the individuals to increase awareness on the conscious use of power. It is a good way to discuss the topic without initiating blame and shame on individuals.

Module 3: Embracing Difference

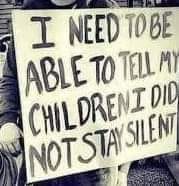

When it comes to embracing difference, our class did touch on the 5 dimensions of oppression (exploitation, powerlessness, marginalization, cultural imperialism, and violence). Similar to Mensah & William’s (2017) boomerang ethics which specifically explores racism, Blumenfield (n.d) shows a similar sentiment on how homophobia has negative impacts on society at large. The common thread of dehumanizing one population segment leading to acceptance of dehumanizing behaviours abroad. That concept brings to light the interconnections of various oppressive practices and why we should not be silent when we are not directly impacted. When Bishop (2015) speaks of collective healing, I think embracing difference and diversity thus becomes a central component in creating the conditions that are needed for an environment where interrelated oppressions can be openly deconstructed. From a perspective that there is a common thread between multiple forms & targets of oppression, the interconnection suggests that there is common ground for multiple population segments to collectively work against oppression – even when it does not appear to have an impact on us at face-value. I believe solidarity, and active participation in deconstructing power structure, speaks to Bishop’s (2015) collectivist orientation by bringing all of us, as community members with diverse intersectional attributes, to the table. Developing our awareness of what is at stake when we do not support the advancement of one another’s rights may help counter the divide and conquer tactics used by those with a greater concentration of power and/or wealth. The lasting impacts of experiential learning interventions that bring awareness to this are demonstrated quite well in interventions such as the one showcased in A Class Divided (PBS, 1985). Working towards social change through embracing difference fits with our professional values of inherent dignity and worth of persons, and pursuit of social justice (Canadian Association of Social Workers, 2005).

Module 4: Colonization & Decolonization

In the pursuit of the dignity and worth of persons and social justice are the complexities of our society and the unjust treatment of First Nations, Métis, and Innuit (FNMI) persons. To begin to develop a decolonizing lens, we must open ourselves up to concepts and experiences that go beyond what we familiar with, and understand how that shapes the realities of those who have experienced oppression through colonization (Heavyshield, n.d). To open ourselves up to unfamiliar perspectives also means that we must be aware of, and ready to deal with, our own biases and assumptions. This module really fit well with the ideas and concepts that emerge from cultural humility (Fisher-Borne, Cain & Martin, 2015), by bringing awareness that there is a need to be more critically aware of the power differentials and accountability to decolonization between the profession, service structures, and clients served with indigenous ancestries and worldviews. The undoing the harm of colonization means educating ourselves and others about the colonizing beliefs we have typically experienced through our socialization process while trying to undo or deconstruct the historical use of power-over on FNMI persons (Bishop, 2015). It also means educating the public about how colonization has gotten us to where we are (here we can apply Foucault and his concept of archeology as to what holds it in place). Embracing culturally relevant practices (such as the smudge we did in class, or talking circles) and developing our own openness to become life learners and advocates through the use of our professional power could be strategies that open up the conversations that would further normalize and promote inclusion of indigenous perspectives in practice. As awareness grows around indigenous perspectives, we can constructively collaborate with populations seeking to continue the work towards social justice by holding governments accountable to respecting the autonomy and rights of indigenous persons, as outlined in the United Nations (2008) Declaration of Rights of Indigenous Peoples. We must also ensure that we work towards ensuring governments at all levels create and maintain policies that fit within the Calls to Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (2015).

To be an adherent to a decolonizing practice, I thought there were several key ideas that came out of this module. The link discussed between harm reduction and decolonizing really stood out because I view the common thread between the two to go back to the critique of western social norms and personal autonomy. Building off that critique was the idea of restorative practice. What I understood in restorative work was that one looks for culturally relevant ways to repair the adverse impacts of colonization (and perhaps impacts of oppression, individualism, and/or capitalism at large). While Cindy Blackstock’s work provides an example of advocacy for equal funding for indigenous children, it also embodies restorative practice by seeking to remove continued paternalistic policies and systems of oppression that restrict the autonomy of indigenous persons (Obomsawin & National Film Board, 2016). The means by which interventions are utilized can thus be very diverse and tailored to the scope of needs for the communities served. In my practice, given my social location and intersectional makeup, consultation and collaboration with individuals and communities would need to be tailored to specific world-views and cultural schemas, so interventions are relevant and not formulated off of a stereotype or colonized frame of reference. Such an approach would seek to enhance the autonomy of the communities impacted. Furthermore, a consultation process may serve to enhance the connections within the community while building relationships between service providers and those who access services.

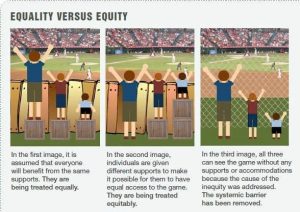

Module 5: Social Determinants of Health

I feel that the social determinants of health fit in well with intersectionality and social location, as many social determinants may be influenced by our intersectional attributes. If we think of the attainment of a highest standard of health as a fundamental right, then our health/social programming is structurally set up in ways that do not provide that right to all individuals. This was exemplified in our class discussions when it came to socio-economic-status, and the varying degrees of barriers that are present or removed as an individual access the system(s). When we think of social justice, Shannen’s Dream (First Nations Child & Family Caring Society, n.d.) was a good example of how structural barriers maintain the status quo and brought to mind this artifact. If we were to remove the structures that delegate a separation of funding between schools on and off nations, we may be able to avert many of the health concerns that arise from infrastructure that does not meet the needs of the respective communities. I feel that the selected artifact demonstrates a way to reconceptualize how to address the social issues around health and human rights by shifting focus on where we try to address the problem. In the case of Shannen’s Dream the question is if the school is the problem, or if the real problem is a the restrictions of autonomy for Indigenous communities that intentionally seek to make a successful, independent, education system viable.

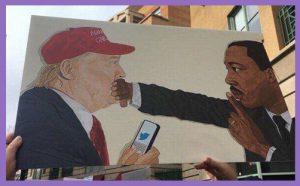

Module 6: Social Justice & Social Policy

This module brought together for me the significance of policy and anti-oppressive practice. The context for social policy is ever-changing, based on the conditions of society at a point in time, but the universalism that was outlined in our discussions on in the powerpoint highlighted to me the importance of policies that forge both universal rights and programming that enhances social functioning (see slides 2, 4, & 5; Boksteyn, 2019). When evaluating social policies, such as the Mental Health Parity in Canada: Legislation and Complementary Measures (Schibli, 2019), there is a really great example of how a position statement can incorporate current policies, as well as evidence-based practise literature that is collective (public healthcare and other social inclusion legislative proposals) oriented. That position statement encompassed factors beyond the biopsychosocial model and included things such as implications of medication and other healthcare costs on social inclusion and wellbeing. That relates well in providing directions for benchmarks that can further guide addressing social problems and outcomes (creating a foundation for evidence-based practice and social justice). The image I have selected as an artifact, a protest sign at a women’s march of “My Brother’s Keeper,” by Watson Mere was selected to outline the significant use of two very different forms of power, and how different power sources can have significant influences on social policy and social justice. One of the individuals in the picture quite articulately (on a regular basis) demonstrates all components of the “Ladder of Oppression” (as cited in Boksteyn, 2019). While America is experiencing more of a shift towards the residual approach ideology in social policy formation, there is no doubt that we are also seeing that in our own country and province as well. One need only look as far as provincial healthcare funding (Health Sciences Association of Alberta, 2019) to see the implications of different approaches on the wellbeing and equal access to services for our population as a whole. For those interested in the implications of social policy, Daveberta and the Broadbent Institute’s Press Progress are two good resources.

Thinking of what Wharf and McKenzie discussed (as cited in Boksteyn, 2019) as professional responsibility in policymaking to ensure social development and social justice are included, I feel that our personal and professional power can play a large role, and it is important to remain grounded in our positions of power (as well as working towards educating others without our professional knowledge on how they can be more grounded). Being aware of intersectionality, and the many faces and interconnections of oppression that are outlined in Bishop’s (2015) work, I come back again to the significance of collective healing that serves as a precursor to both social justice and social policy. While recognizing the ebb and flow of trends in social policy, it is arguably also equally important to facilitate the formation of the conditions where socially just policies are embraced throughout the broad population, so that “power-over,” even if it addresses structural inequality, does not quickly dissolve and the policies that were created to enhance our community equality quickly disappear. To me, that can also highlight the power of fostering an environment of solidarity, so that groups experiencing a loss of privilege do not feel alienated and reactionary. For myself, that means a long-term adherence to raising awareness to both policymakers and community members the impacts and interconnections of SCRAP (sexism, classism, racism, ageism, poverty, and unmentioned others such as ableism and colonialism/imperialism) to their own wellbeing and prosperity (as cited in Boksteyn, 2019). Furthermore, it means the promotion of our core value of social fairness that recognizes and seeks to address the barriers that exist for those who experience various vulnerabilities while challenging the assumptions or stereotypes placed on groups (Canadian Association of Social Workers, 2005).

Module 7: Social Action

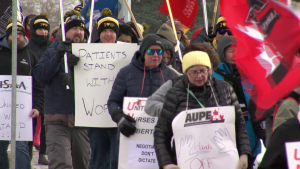

Thinking to the three models of community change (community development, social planning, and social action), I feel that our approach to community change is mediated by our access to power, along with our professional recognition as stakeholders in the community. While the community development model seeks to strengthen relationships and resource access through collaboration between service provider stakeholders, social planning seeks to rationally implement policies that are established as sound through an evidence base (Parada, Barnoff, Moffatt, & Homan, 2011). Both work within the system to reform it and address the needs of a community. The question is what can be done when those in positions of power guide or establish policies for the system that neither seek an evidence-base for support nor seek to improve the conditions that would foster enhanced capacity to collaborate in service delivery. My ideological orientation naturally makes the third option, social action, or the pursuit of engaging in activities to promote fundamental changes to social structures, organizations, and economic systems a morally appealing option (Parada, Barnoff, Moffatt, & Homan, 2011). That is notably also influenced by my own privilege and freedom to partake in social action without fear of repercussions at a personal or professional level at this point in my life. I think what was mentioned in class about constructive, non-aggressive, social action is critical (One could use Martin Luther King Jr. as a good exemplification of that strategy). As an artifact, I selected a photo from the Medicine Hat Hospital Union information session because it fit well within solidarity between various unions and community members while recognizing the implications for both service users and service providers. It can furthermore be an empowering experience for workers to see that their voices can be heard by members of the public while they advocate for a quality healthcare system for service-users. The defunding component fits well with the spirit of the content of what Bishop (2015) outlined in the enclosure movement. Being invited by union members made the experience a worthwhile act of solidarity and provided an opportunity to listen to the concerns of workers.

Course Content & Reflexivity on the Social Work Identity

I found that the teachings from both courses fit quite well with my own value system and reaffirmed my identity within the social work profession. One of the primary learnings I will bring into practice is the idea that it takes experiencing oppression to become an oppressor (Bishop, 2015). Considerations like this are important in work that aims to identify and change the course of turning points that can negate ideological polarization and social fragmentation that contributes to social disorder (Winter & Feixas, 2019). Within an anti-oppressive practice context, this broadens by the scope of how I look to identify oppression, as well as using my own value and belief systems to tap into empathy for those with greater power whom I may have before only conceptualized as oppressive agents. In addressing those personal biases, I think that creates the conditions to not “other” individuals using “power-over,” allowing for more constructive work on creating the conditions needed to address oppression. This approach would allow for me to better adhere to the CASW’s pursuit of social justice by actively seeking to advance social development that is in the interests of all people, by trying to set the conditions for win-win scenarios (Bishop, 2015).

When thinking of working to establish a win-win environment it frames the context of what anti-oppressive practise seeks to achieve, namely the maintenance or formation of universal rights (Canadian Association of Social Workers, 2018; Bishop, 2015). This fits well with the ideas presented by Blumenfield (n.d) on homophobia and its impacts on all. I was initially leery about using the self-interest of those in a position to oppress one group as a means to justify the cessation of oppression. In another sense, it may provide a starting point for those who have not thought about how there is an interconnection between oppressions. This has reframed how I look at trying to build cohesion and solidarity. However, I don’t expect this to be a seamless process of ending oppression. It would need to be partnered with the individuals each being set up to find their own sources of oppression, liberation, and then come to a point where there is a genuine interest in partaking in collective healing (Bishop, 2015).

We can not discuss collective healing, however, without consideration and consultation with individuals with an FNMI ancestry as stakeholders at the table. As has been outlined, the historical context of relations continues to shape the nature of the relationship and frames of reference in how we address the social issues at hand. Part of the decolonization process includes reflexivity on our own colonized frames of reference they may be dependent on the systems that are already in place. To commit to restorative practice as a form of social justice to me means recognizing paternalistic and colonizing attitudes that show their face through policy and legislation. Our role as advocates from an anti-oppressive framework of practice thus depends on reconceptualizing the conditions for autonomous governance and sociopolitical partnership at a macro level (see Colonization and Restorative practices; Heavyshield, n.d.). This provides guidance in practice as to where we begin to look at both restorative antioppressive practice from a structural lens. It also means fostering solidarity with allies to promote the advancement of policies that normalize the decolonized worldview and indigenous ways of knowing.

In conclusion, the role of social justice, as outlined by Gary Craig, seeks to foster acceptance of diversity, dignity, and basic needs, while seeking to improve equality and participation of all within society (as cited in Lundy, 2011). As has been explored, there are many facets of society that can be analyzed and critiqued to fit within the scope of the antioppressive mindset. However, critique alone is insufficient to adhere to the spirit of antioppressive practice. As outlined by our classes, my reflection, and the spirit of Bishop’s (2015) work, our actions that promote environments that foster hope and liberation from oppressive structures are just as important to set up the conditions needed to facilitate change directed by the people.

References

Bishop, A. (2015). Becoming an Ally Breaking the Cycle of Oppression in People (3rd ed.). Halifax; Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing.

Blumenfield, W. (n.d.) How homophobia hurts everyone: A theoretical foundation. Retrieved from http://www.uas.alaska.edu/juneau/activities/safezone/docs/homophobia_harmful.pdf

Boksteyn, L. (2019). Social Policy UofC Learning Circles [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from https://s3.ca-central-1.amazonaws.com/d2l-docbuilder-prod-ca-central-1-converted/e44b674e-6939-4b63-98a6-599048d00fab/bdc2e7aea9b6e741cdae657bdd0a26ea.pdf?X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Credential=AKIAJOEGJFTCS3IHJNWA%2f20191122%2fca-central-1%2fs3%2faws4_request&X-Amz-Date=20191122T010520Z&X-Amz-Expires=900&X-Amz-Signature=45b1a26b69d66e7b5b283684ba05125075106e0f8bf8fa08aa9158bf6e83c04b&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=host

Boksteyn, L. (2019) Social action: University of Calgary BSW learning circles November 2019 [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from https://s3.ca-central-1.amazonaws.com/d2l-docbuilder-prod-ca-central-1-converted/e44b674e-6939-4b63-98a6-599048d00fab/ac0d2701e643080d94a72d46c9cd30fe.pdf?X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Credential=AKIAJOEGJFTCS3IHJNWA%2f20191122%2fca-central-1%2fs3%2faws4_request&X-Amz-Date=20191122T011100Z&X-Amz-Expires=900&X-Amz-Signature=8d084fb61be73959ddd32c43639100c4790a2ae56fb0d8598c6b40ade661f9f9&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=host

Canadian Association of Social Workers. (2005). Code of ethics. Retrieved from https://www.casw-acts.ca/sites/default/files/attachements/casw_code_of_ethics.pdf

Canadian Association of Social Workers. (2018). Critical social work: Past, present, and future. Canadian Social Work 20(1). Ottawa, ON: Canadian Association of Social Workers.

Castillo, Richard J. Culture mental illness: a client-Centered approach. Brooks/Cole Publ, 1997.

Cocker, C., & Hafford-Letchfield, T. (2014). Rethinking anti-discriminatory and anti-oppressive theories for social work practice.

Fisher-Borne, M., Cain, J. M., & Martin, S. L. (2015). From mastery to accountability: Cultural humility as an alternative to cultural competence. Social Work Education, 34(2), 165-181

First Nations Child & Family Caring Society. (n.d.). Shannen’s Dream. Retrieved November 24, 2019, from https://fncaringsociety.com/shannens-dream.

Foucault, M., & Sheridan, A. (1995). Discipline and punish : The birth of the prison (second edition). New York: Vintage Books.

Health Sciences Association of Alberta. (2019, October 25). Media release: The truth hidden in Kenney’s “cuts-upon-cuts” budget. Retrieved November 15, 2019, from https://www.hsaa.ca/2019/10/25/media-release-truth-hidden-kenney-cuts-upon-cuts-budget/.

Heavyshield, H. (n.d.) Colonization and restorative practices [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from https://s3.ca-central-1.amazonaws.com/d2l-docbuilder-prod-ca-central-1-converted/e44b674e-6939-4b63-98a6-599048d00fab/24b0231e8e2fce3d727176751543402e.pdf?X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Credential=AKIAJOEGJFTCS3IHJNWA%2f20191123%2fca-central-1%2fs3%2faws4_request&X-Amz-Date=20191123T000249Z&X-Amz-Expires=900&X-Amz-Signature=d24659e94c304198f7db956deea31dc0fb22c363a21fff7af7f78ccb65eff405&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=host

Lundy, C. (2011). Social work, social justice & human rights: A structural approach to practice (2nd ed.). North York, Ont.: Univ. of Toronto-Press.

Mattsson, T. (2014). Intersectionality as a useful tool: Anti-oppressive social work and critical reflection. Affilia, 29(1), 8-17.

Mensah, J., & Williams, C. J. (2017). Boomerang ethics: How racism affects us all. Halifax: Fernwood.

Neckoway, R., Brownlee, K., & Castellan, B. (2007). Is attachment theory consistent with Aboriginal parenting realities?. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 3(2), 65-74.

Obomsawin, A., & National Film Board. (2016). We can’t make the same mistake twice (video file). Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IJoXQxK2n5s

Parada, H., Barnoff, L., Homan, M. S., & Moffatt, K. (2011). Promoting community change: Making it happen in the real world (1st Canadian ed.). Toronto: Nelson Education.

PBS Video. (1985). A Class divided [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1mcCLm_LwpE&t=224s

Schibli, K. (n.d.). Mental health Parity in Canada: Legislation and complementary measures. Retrieved November 10, 2019, from https://www.casw-acts.ca/sites/default/files/attachements/Mental_Health_Parity_-_Final_Paper.pdf.

Shebib, B. (2017). Choices: interviewing and counselling skills for Canadians (6th ed.). Toronto, ON: Pearson.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Volume one: Summary. Toronto: James Lorimer & Company.

United Nations. (2007). United Nations declaration on the rights of Indigenous peoples. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf

Wenger-Nabigon, A. (2010). The Cree medicine wheel as an organizing paradigm of theories of human development.

Feixas, G., & Winter, D. A. (2019). Towards a constructivist model of radicalization and deradicalization: a conceptual and methodological proposal. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 412.